I danced my way to the top of Kilimanjaro.

It was the last stop on my unofficial Five Summits Tour of East Africa. In the span of two months across Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania, I hiked the Rwenzori Mountains, and summited Mount Elgon, Mount Kenya, and Mount Meru.

I felt better than good. I felt alive. Two months earlier I left the U.S. feeling burned out and sick. But by this point I was in such good shape that Kilimanjaro was a piece of cake. I hiked the entire way breathing easily through my nose, and never once felt sore or exhausted. As we neared the summit, I felt like I could do anything.

"You are a simba," said Baraka, our assistant guide.

"What do you mean?"

"A lioness. Strong. Courageous. You could be a guide."

I smiled. It wasn't the first time I'd been told this, but it was the first time that the observation from the outside reflected my own. For the first time in a long time, I felt good in my body. Healthy, strong.

But I knew that after two, miserable night summits on Mount Kenya and Mount Meru, I still had a big challenge left to overcome.

I've got this.

I hope.

Baraka, our assistant guide, in the center. Kilimanjaro's Lemosho route starts like any other hike, in the trees. 🌳

"How can I make this better?"

I'm sitting across from the owner of the tour company I booked my 8-day, Lemosho-route Kilimanjaro trek with. Mr. Shah looks at me, concerned.

Earlier that day, the head guide had arrived at my accommodation for the pre-trip briefing and gear fitting, and something... was off. He hadn't brought any of the gear. He didn't give much information about the hike – except to make sure that I knew tips were expected. 🤦♀️ When I asked questions, he seemed a bit slow, like he was fumbling for the right words.

"Can you walk me through each day? I want to make sure I understand the distances and elevation gain."

"You will go at your own pace. At times I might walk behind you."

Walk behind me?

I realized maybe he had misunderstood. I asked what time we would start in the morning. He said that he wasn't sure.

"Can you come back later with more information and the gear?"

"In the morning."

"I'd rather have it sorted today?"

He left, visibly disgruntled by my request, and returned a few hours later with only half of the gear I had rented through the company.

"Where's the rest?"

"Tomorrow," he said, noting the look of worry on my face, "Don't worry."

Too late for that.

He left again. I still had no information about the logistics of the trip. I felt a knot forming in my stomach.

I've been here before.

Immediately my disastrous Mount Kenya hike comes to mind. The last time my guide gave me no information? He let me walk my way into altitude sickness.

Am I really about to hike for eight days into the highest elevation I've ever been in with no information or preparation?

Do I really trust this guy to get me there?

I pulled out my phone and sent a quick email to Mr. Shah, explaining that I had some concerns about my first impression of the guide – and requested him to come by my accommodation at his earliest convenience.

Now he's sitting across from me, waiting for an answer about how to fix it, and I hesitate.

"Perhaps we should change the guide," he wonders aloud, looking at my face for confirmation that this is the solution I want.

I say nothing. I watch him mull it over while I remain expressionless. My mind spins its calculations. Do I want a different guide? Sure – if there's a better one available. But I don't want to be the reason that someone loses work. What do I say?

"I don't want him to be out of work. I just want to make sure that we're prepared and in good hands for the next eight days."

"Let me sort things out, and I'll come back later," he concludes, leaving me to sort out my thoughts.

Note to self: If the guide loses work, I am not the reason. The guide is. I am paying thousands of dollars for this hike. I deserve better.

A few hours later Mr. Shah returns. He has a folder. With slides. He spends about 20 minutes walking me through the itinerary for each day, and then he informs me that he has changed the head guide, and thrown in a private toilet "for the trouble."

"Oh, really it's okay, we don't need that," I reassure him.

"Well," he presses, "you do. Trust me. It will make your experience a lot better. The shared toilets aren't maintained by the national park. This one comes with a porter to clean it. Also, it will give your support team the flexibility to set up camp wherever they want, instead of fighting for space with the other tour groups to get close to the toilet block."

"Oh, well alright then. Thank you."

In hindsight, I can't imagine hiking without the replacement head guide, Stanley.

Stanley is a multiple-Guinness-World-Record-holding skyrunner.

Skyrunning is trail running above 2,000 meters.

Stanley does it at 6,000. 🤯

Four months before our Kilimanjaro summit, Stanley ran it. Actually, not only did he run it – he ran 53.6 kilometers of it. Stanley completed the World's Highest Ultra Marathon, which entails running from 4,895 meters up to the Uhuru Peak summit of 5,895 meters and then running back down the mountain for a total descent of 4,800 meters to the finish.

My jaw drops.

"You think that's cool," says Stanley, laughing, "Most of the porters and some guides compete in an unofficial Olympics that takes place in the crater over a few days in the low season."

The crater is at ~5700 meters. A few days, he says, of camping out and competing in obstacle courses and relay races.

Yeah – I think we're in better hands with Stanley than with the guy who wanted to walk behind me.

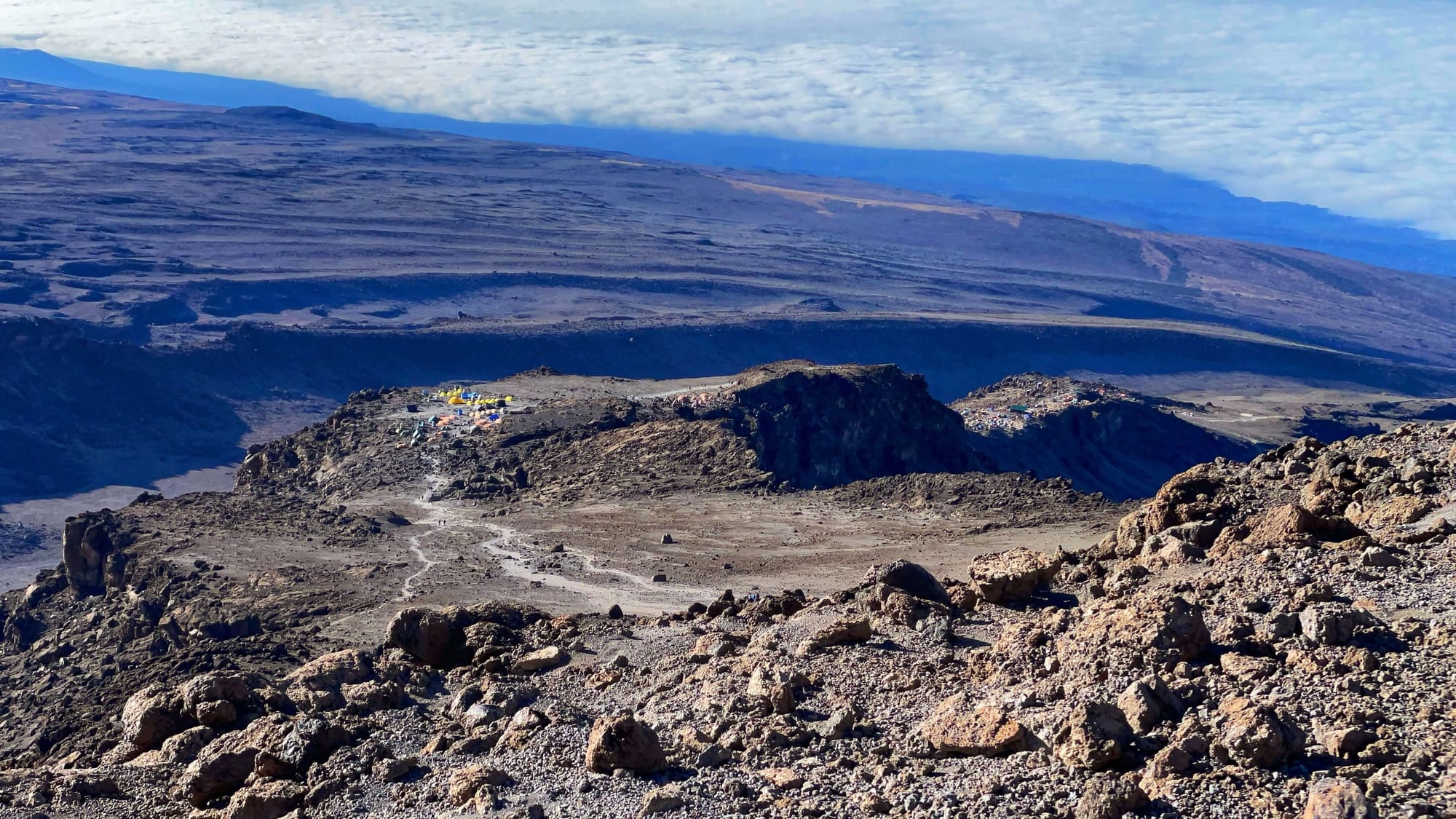

Shira Peak is the lowest of the three peaks of Kilimanjaro. We will see Mawenzi from our final camp before the summit of Kibo. | Click any image to view larger.

Over the course of the eight days we spend hiking Kilimanjaro, Stanley tells us all sorts of fun facts about the mountain that I can't remember now, but I remember appreciating in the moment. As the great Maya Angelou put it:

"I've learned that people will forget what you said, people will forget what you did, but people will never forget how you made them feel."

With Stanley, I felt love. His love for the mountain rubbed off on us. He showed us views and vantage points that he loved even on the thousandth time he'd seen them. He reminded us that the Swahili motto pole, pole (slowly, slowly) was as much about acclimatization as it was about enjoying the experience.

"This is probably the only time in your entire life that you'll be on this mountain," Stanley reminds us. "Take your time and enjoy it."

After Shira Peak, we traversed the stunning alpine desert of Kilimanjaro. | Click any image to view larger.

Giant Groundsels are the cactus-like plant in the alpine desert. | Click any image to view larger.

While the Americans behind us were busy inventing a new talk radio show, our little pod was busy falling in love with the experience of being on the mountain with Stanley.

Later that night at dinner, one of the Swiss guys brings up the original head guide, and I explain what happened.

"Thank you," he says, and the other one nods in agreement. "That other guide was either drunk or hungover when he came to our place. We weren't sure if we should say something. I'm glad you did."

"I can't imagine hiking with that other guide," the other guy says. "This hike would have been a totally different experience."

I nod. "I'm glad we have Stanley."

"And that toilet. Thanks for getting us that too. Had no idea we'd need that – and we need it."

We laugh. He hasn't been acclimatizing so well – and he's become friends with the toilet (and probably enemies with the porter responsible for it).

That night as I lay in my sleeping bag, I reflect on their gratitude for speaking up – and tried to reconcile it with the inner turmoil I had felt when doing so.

Our trek is noticeably better because I said something. Because I said "this is not OK" and in doing so, created an opportunity for the situation to get better.

For the first time that maybe I could ever remember, I didn't dismiss my experience, or sacrifice my needs. I trusted my instinct, and I stood up for myself.

And when I advocated for myself, I made the experience better for others too. They thanked me for doing what they wanted to do, but didn't.

I deserve to bask in that same gratitude for myself for showing up for myself.

I made this happen. And I don't ever want to silence my inner voice or second-guess myself again.

On the night of the summit, I pick my playlist, and start to dance to it as I get in the zone while watching the moonrise over Mawenzi Peak.

Six faces of sunset on Mawenzi Peak, Kilimanjaro. | Click any image to view larger.

"We will leave at 12:30," Stanley announces at dinner.

"12:30?" I am skeptical. "Aren't the other groups leaving at 11?"

"Do you want to stand at the top in the cold?"

"No, but..."

"You are fast. Trust me."

The Swiss guys shrug. They're happy for more sleep. I know that I'm not going to sleep anyway – and worried about missing the sunrise like I did on Mount Kenya.

Just after midnight, we wrestle with our layers, "eat breakfast" and then leave camp.

There's a queue.

A long one.

Of everyone who left at 11.

I stare up the mountain at the little dots of headlamps that reveal the switchbacks the whole way up.

Stanley clocks my dejected face.

"Follow me."

He steps off of the trail into the lava rock and starts to walk straight up it.

The Swiss guy with the stomach problems isn't happy.

"Are you kidding?"

But we follow. Stanley says hello to the other guides leading their tour groups up the switchbacks as we sail past them in a beeline toward the top. Eventually, the Swiss guys plead for a break.

Stanley and Baraka evaluate the group.

"I think we should split up," Stanley says. "I'll take her to the top and you can take the boys at your own pace."

"You can go faster with them if you want," the Swiss guy with the stomach problems offers to his friend.

He agrees – and then the three of us are off.

I put in my headphones and start dancing to my playlist as we pass more tour groups. I'm not the only one with the music idea; "Don't Worry Be Happy" and "Eye of the Tiger" blare through portable speakers as we pass more tour groups. The Swiss guy who came with us immediately regrets his decision.

"How... are... you... dancing..." he pants, out of breath.

It isn't until we reach Stella Point – the last rest stop before we push to the top – that my stomach begins to flip. I plop myself on a boulder and announce that I need a "lil snack."

"No," Stanley says firmly. "You're going to make him cold."

He points at the Swiss guy who does, in fact, look cold. I sigh, get up from my rock, and we keep going.

Thirty minutes later, at 5:50 AM, we reach the summit.

I see the sign for Uhuru Peak and I hand my phone to Stanley as I boogie my way to it and give it a big smack. He takes a bunch of photos. It's only after I give up my spot to the Swiss guy that I realize – we're the only ones up here.

By a long shot.

Not only did we make it. We literally passed every single tour group on our way up. I'm shocked that Stanley knew – and even more impressed with his skills as a guide.

There's no way I would have made it up to the top first – and in record time – if we had that other guy as our guide.

We still stood around for an hour in the bitter cold though. 😂 We couldn't miss the light show – or the chance for a group photo when the other two finally joined us.

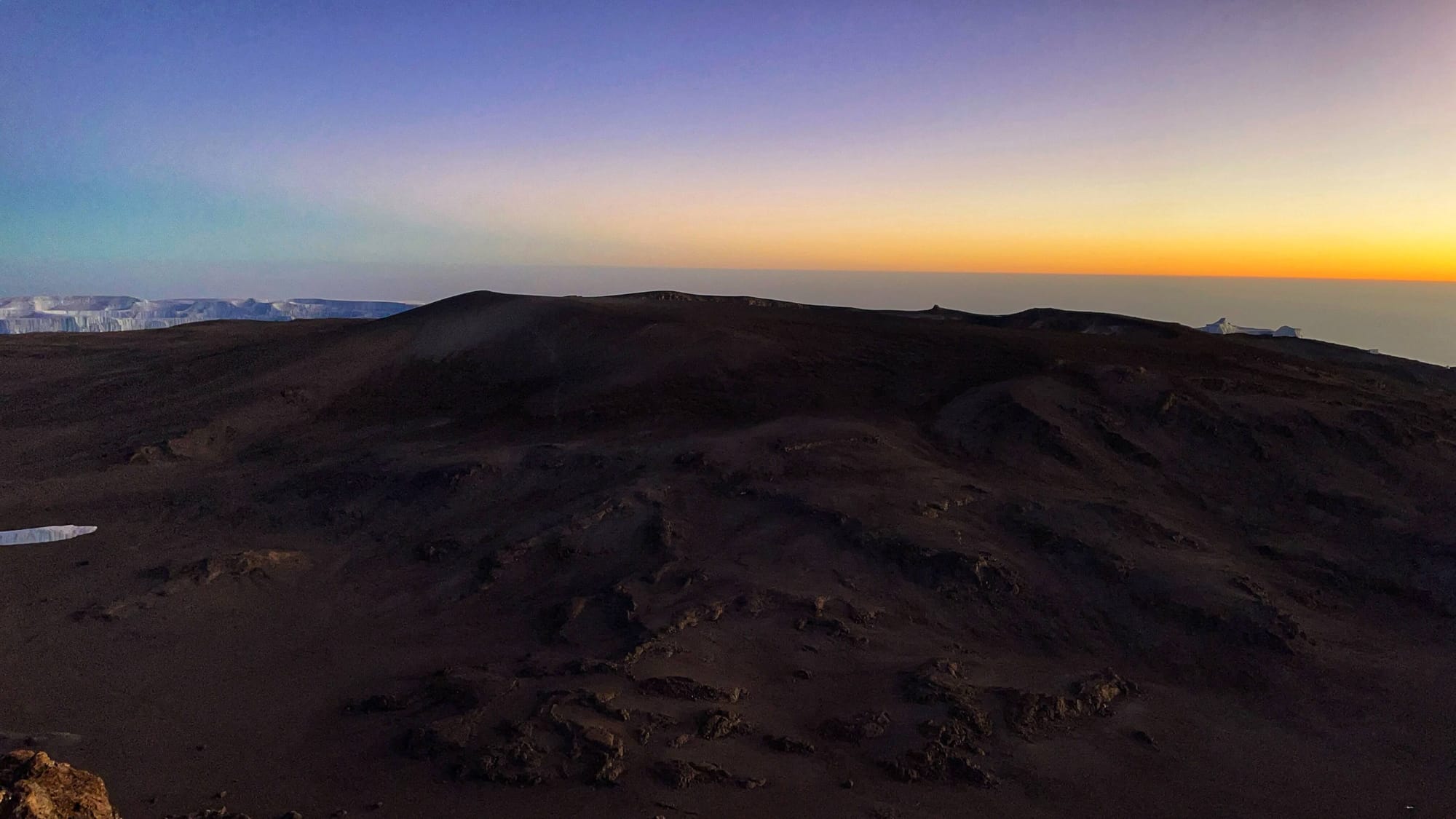

I know you can't exactly time it, but if you can make it up for first light, you will get an empty summit and the pastel hues that paint the sky like this. It's really an unparalleled view. Here you can see a glacier (the "Southern Icefields"), and Mount Meru. | Click any image to view larger.

I wish I could say that the dance party continued on the way down, but at some point, the adrenaline rush subsided and exhaustion kicked in. It was a brutal push down to the lower camp, and if I hadn't been locked into the tour itinerary, I would have wanted to stop sooner, to bask in the achievement of the day, and start fresh again tomorrow.

This was all in one day of hiking. The same day we did the summit. 😩

The day after the summit, we exited through the rainforest, they handed us our certificates, and it was over.

I wasn't sure how I felt about the abrupt ending, or what to make of the experience yet. Instead of integrating, I felt myself disintegrating. I had come down, but I hadn't "come down."

My heart was still somewhere on the mountain, in the experience of myself as a woman of strength and courage, longing for just a little bit more time.