It wasn't the force of the water that knocked me back to consciousness, though it swirled and whipped me like the contents of a blender, leaving bruises that would take weeks to recover.

It was when I felt the toe of my shoe get stuck in a rock that I thought:

I might not survive this.

As soon as the thought crossed my mind, another one took its place.

No. Not today. This is not my time to die.

And I wiggled my heel out of the strap, leaving my shoe behind as I fought my way to the surface for air.

I took one breath before the water from the rapid engulfed me once more, this time, sucking me under the raft. I fought again to reach the surface, but when I did, I gasped for air and instead choked on water. I couldn't find a steady gap for air, with the way the water crashed into the underbelly of the raft. I needed to breathe.

Oh my god, is this it?

Twice now the thought has crossed my mind that I might die – a thought I have never had before, not even when I was fighting for my life in the hospital. And I was horrified by this being my ending.

I did not survive everything I've been through to die like this.

Submerged by the churn of the water, I swam again with all my might in a different direction, and this time I found myself just outside the raft. I gulped the air, but could only take one breath before I was sucked back under again in the tumult.

I don't know how I eventually got out. I don't even remember the moment we flipped. All I know is that the flip happened at the very beginning of the rapid, and it wasn't until we cleared the whole thing that I finally came to the surface. I was the first one to make it back into the raft, because I was the only one stuck under it.

Later, when I would see the pictures that were taken from the shore, I shivered at what they might have documented. In a series of 50 photos, about 5 photos in, you see the raft flip. Then as each photo progresses, you see the people popping up to the surface, buoyed by their life jackets, floating with their feet up through the rapid.

But you don't see me. Ever. Not until the very end.

And it's not lost on me that there is another version of the story where the me that pops up in the last photo is simply my body.

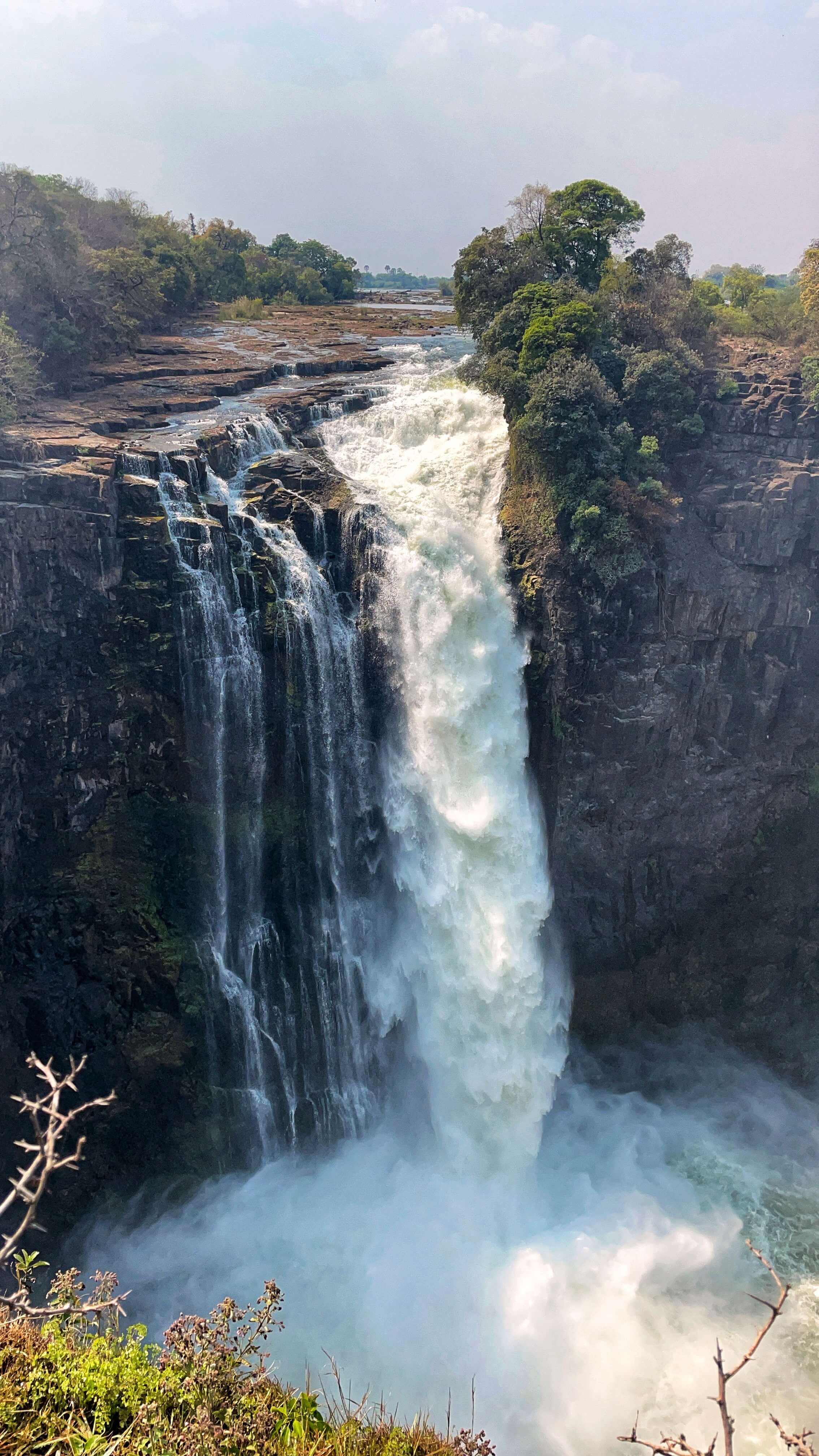

Victoria Falls is long. So while the birds-eye image above doesn't show much water, that's only because it is dry season, so that part of the flow is more of a trickle. From where I stood to take the photo, around the bend to the left and behind me is where all of the water is. Like this section in the video.

Africa's Victoria Falls is one of the most popular whitewater rafting destinations in the world. So popular, in fact, that when I went to an REI store in Reno, Nevada to try out inflatable sleeping pads for my backpacking adventure, the guy who helped me said, "Make sure you go whitewater rafting at Vic Falls and stay at Jollyboys [hostel]!"

Even though it features Class V rapids – the highest level of difficulty for commercial rafting trips – it is advertised as a safe, family friendly activity. I'd been whitewater rafting twice before, so I didn't expect the trip to be any different. I booked with a popular, licensed tour operator. I had never flipped on previous trips, and I had no reason to expect that we would on this one.

Apparently, flipping while rafting Victoria Falls is common.

What I hope isn't common is the hurried safety briefing that my group received, and limited instruction about how to paddle as a unit. Immediately, I was concerned by the lack of direction, but I quelled my fears thinking, we'll get the hang of it before the first rapid.

The guide assigned places in the raft, and I was given the spot in the back, opposite him, even though I was one of the lighter people in the group. I spoke up about the weight distribution, and he said, "Would you rather be in the launch seats?"

"I definitely don't want to go in."

He pointed his hand at the seat across from him expectantly, and we took off.

There was no time to get the hang of paddling in rhythm before the first rapid, which was only about a minute down the river. I knew something was wrong when we entered the rapid and instead of barking orders to get us to paddle in sync, the guide shouted "hang on!" – the signal for ducking into the raft and clutching the ropes.

That's not what you say to a team that's supposed to paddle through a rapid. That's what you say when you've already lost control.

Each rapid we approached, he would tell us to "hang on" to go through it. When we reached the fourth rapid – which I later found out is supposed to be approached by paddling around it, and entering from the right side – we went straight through the center at a slight angle, and immediately flipped.

If I'm making it sound like my guide had no clue what he was doing, or no interest in our safety, it's because that's how it felt. He knew this river. He knew that rapid. He knew exactly what we were in store for. And he never even tried to coach us through it.

We never had a shot of not flipping – and he didn't prepare us for how to survive it when we did.

Even though I saw the red flags, all of this happened in about 20 minutes, briefing to flipping. In hindsight, should I have opted out of the trip? But how was there any time to make a different choice?

It was irresponsible of my tour company to not prepare us for the reality of flipping, which sounds silly, of course you might flip, but I was operating under information from previous experiences, where flipping was uncommon, "only if something goes really wrong." The tour company took my money without educating me on the risk of the activity I was booking – and didn't leave me an out when I finally realized what could happen.

Ultimately, though, I don't think the problem is a careless guide or a lackadaisical tour operator. My experience is reflective of a broader attitude I witnessed around safety in post-colonial countries.

Do you see where that guy is standing in the center of the first picture? That's where I am in the second. No, this Instagram moment would never happen in the States. | Click any image to view larger.

Over the 15 months I spent backpacking around the world, I observed a pattern in every post-colonial country I visited: people often ignore basic safety precautions that the West would consider the norm. Seatbelts in cars? Helmets on motorbikes? Life jackets on boats, where most of the local population can't swim? No. No. And no.

This isn't about access, though you could make that case about helmets – that perhaps people forego them because they can't afford them. But the seatbelts exist. And I've literally watched life jackets be left behind. I think there's a deeper story here about how people view the value of their own lives – a story shaped by centuries of being treated as bodies for work, worked to death, replaced as easy as they were disposed.

Centuries of being told that your life matters less embeds into the culture and psychology of a people.

The way people in eastern and southern Africa treated me as social currency, wanting selfies with me ("new profile pic") to heighten their clout simply because of the color of my skin, signals internalized racism. Of course this would extend to safety too.

Notice how the waterfall isn't even in the pic the girl's friend took? That's because I am the main attraction. 😭 My pic from the same spot is on the right, with the rainbow. | Click any image to view larger.

I think this is as much about the devaluing of human life as it is about a heightened collective risk tolerance. There's danger – that many of you reading this don't face on a daily basis – to living in a society that either can't (no tax base) or doesn't (corruption) invest in public health and safety, from roads not maintained, to tropical diseases that claim lives. Perhaps it is the desensitization to risk, coupled with the government's laissez-faire approach to enforcing safety laws, that has shaped cultural norms of relaxed behavior around safety.

Because that's really what I think happened on this whitewater rafting trip. I don't think anyone set out to make the trip unsafe. I just don't think anyone took our safety seriously before throwing us into dangerous waters without adequate preparation. And to them, perhaps the safety briefing was already doing a lot more than they would have, had the trip been filled with locals.

It begs the question about what it means to care for yourself when the system you are living in doesn't.

We know that culture isn't a panacea, that the expression "That's just the way it is" is used silence individuals whose intuition says, "This is not how I want to live."

How can individuals be empowered to make different choices around their own health and safety, and not be ostracized by the collective? If a seatbelt was accessible to me, I wore it – but not without shame and judgment from watchful eyes for doing so.

What about a local who wants to go against the norm? "Doing the right thing" or even "protecting my family" isn't enough to overcome pressure from a collective that doesn't care – even if the attitude is rooted in systems of racial harm.

Safety is the fertile ground from which life blossoms. Children explore, learn, and grow when they feel safe. And the thing about safety is that no amount of grit can override it. If your nervous system thinks you are not safe, all of your energy is directed toward survival, and away from the activities that give life meaning and joy.

How many people consciously or subconsciously don't feel safe on a day to day basis, and thus can't live up to their potential?

I met far too many children and adults in Africa with stories of educations that cut short when they were reprimanded and even beaten for asking questions. They stopped engaging with the world because they no longer felt safe to do so. Punishing children for asking questions in school trains them to remain silent.

And I wonder how many of them would speak up about safety, if they felt safe doing so.

After we made it back into the raft, various parts of my body started to swell as the blood rushed to heal what had been wounded. I tried to paddle, but it hurt my hand too much, and I was shaking uncontrollably with fear. We were only four rapids in, with twenty something more to go, and I was terrified that we would flip again. I wanted out. But there was no out. Even if I wanted to hike out, there was no escape route up the vertical rock face of the canyon walls. The only way out was to keep going down the river. To persist, and override the voice screaming inside of me to stop.

There wasn't a single moment of the whitewater rafting trip that I enjoyed.

I'll never go whitewater rafting again.

And that's a privilege I have that not many people in the world do.

I get to choose to remove myself from unsafe situations.

I get to choose not to survive, but to live.